North to Shore Festival Maps Musical Journey Across Jersey

The multi-venue festival celebrates New Jersey's rich musical heritage from the Meadowlands to the shore, showcasing homegrown talent across iconic venues.

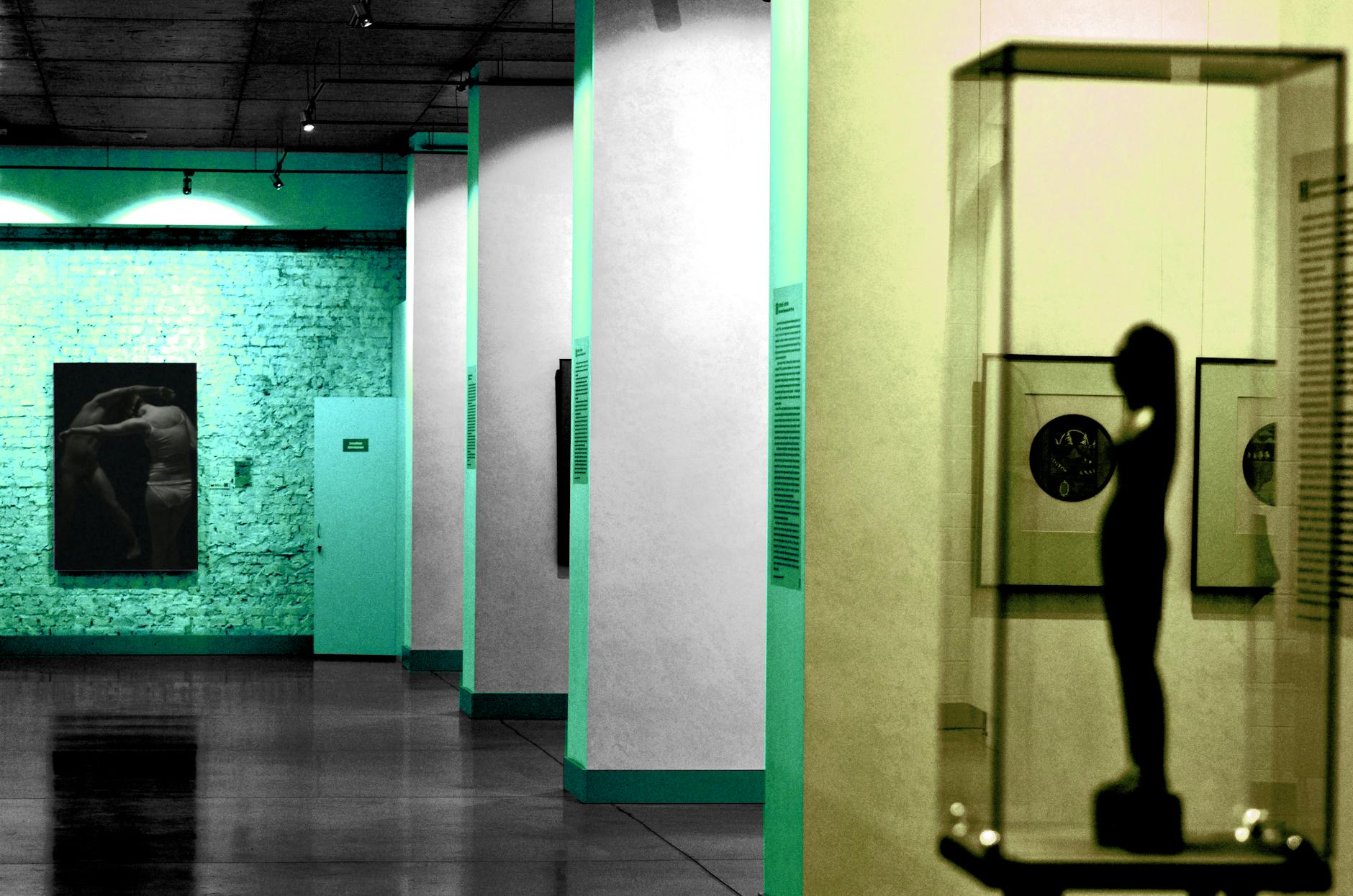

The first chord strikes at a warehouse venue in Newark, and by the final encore three days later, the music has traveled the length of New Jersey’s musical soul — from urban clubs to shore boardwalk stages where legends were born.

The North to Shore Festival, returning this June after a pandemic hiatus, isn’t just another music festival. It’s a musical pilgrimage that traces the state’s sonic DNA, connecting the dots between the gritty club scenes of North Jersey and the storied venues that made the Shore a launching pad for American rock and roll.

“New Jersey doesn’t just have music venues — we have musical holy ground,” says festival director Maria Santos, standing outside the Stone Pony in Asbury Park, where Bruce Springsteen still occasionally drops in unannounced. “This festival is about showing people that journey, that connection between where music starts and where it becomes legendary.”

The festival’s concept is uniquely Jersey: rather than cramming dozens of acts onto a single site, North to Shore spreads performances across 15 venues from Jersey City to Cape May over four days in mid-June. Festival-goers can buy single venue tickets or full passes that include charter buses connecting the locations.

This year’s lineup reads like a love letter to New Jersey’s musical diversity. Punk legends from the Misfits’ hometown of Lodi share stages with indie bands from Princeton’s vibrant college scene. Hip-hop artists from Newark and Trenton represent alongside folk musicians from the Pine Barrens. The closing night at Asbury Park Holiday Bazaar Draws Crowds to Historic Convention Hall features three generations of Jersey musicians, including several Springsteen collaborators and members of Bon Jovi’s early touring bands.

“What makes this special is that every venue has stories,” explains longtime New Jersey music journalist Tom Rodriguez, who’s documenting the festival for a planned book about the state’s music scene. “You’re not just seeing a show at the Starland Ballroom in Sayreville — you’re seeing it where My Chemical Romance played their first major show, where Thursday recorded a live album, where a thousand bands cut their teeth.”

The festival emerged from conversations between venue owners during the early pandemic, when empty clubs across the state faced uncertain futures. Rather than compete for the same touring acts, they decided to collaborate on something that celebrated their collective history.

Middlesex County’s venues anchor the festival’s middle section, with stops planned for New Brunswick’s legendary basement clubs and the Stress Factory comedy club, which will host a special music-meets-comedy night featuring New Jersey comedians and singer-songwriters.

For Santos, whose family moved from El Salvador to Union City when she was eight, the festival represents something deeper than entertainment. “I grew up going to shows at Maxwell’s in Hoboken, taking the PATH train from my neighborhood where everyone spoke Spanish to this place where music was the universal language,” she says. “That’s what New Jersey music is — it’s everyone’s story mixing together.”

The economic impact extends beyond ticket sales. Hotels from Newark to Cape May are offering festival packages, and local restaurants are creating special menus for each venue night. The New Jersey Tourism Board estimates the festival could bring $12 million in economic activity to participating communities.

Logistically, the festival presents unique challenges. Weather contingency plans include indoor backup venues, and the charter bus system requires coordination with local police departments across seven counties. But organizers say the complexity is worth preserving the festival’s geographic storytelling.

“You could put all these bands in MetLife Stadium and call it a day,” Santos admits. “But then you’d miss the whole point. The magic happens when you’re in a 200-person club in Hoboken at 1 AM, and you realize the guitarist grew up three towns over from you, and suddenly New Jersey feels both huge and tiny at the same time.”

Early bird festival passes go on sale next month, with partial proceeds benefiting the New Jersey Music Venues Recovery Fund, which provides grants to small venues still recovering from pandemic closures.

For music lovers who’ve long argued that New Jersey’s contributions to American music go underappreciated, North to Shore offers vindication. The festival doesn’t just showcase New Jersey musicians — it celebrates the places that shaped them, the venues that gave them their start, and the geographic journey that turns local bands into cultural exports.

“People think of us as New York’s backyard or Philadelphia’s suburb,” Rodriguez says, watching sound crews set up at the Stone Pony. “But when you trace the path from Newark to Asbury Park, when you see how music moves through our state, you realize we’re not anybody’s backyard. We’re the main stage.”