Newark's Prudential: Most NJ Workers Unprepared for Retirement

New research from Newark-based Prudential shows middle-class New Jersey workers face a retirement crisis, with many lacking basic savings plans.

Middle-class workers across New Jersey are sleepwalking toward a retirement crisis, according to new research from Newark-based Prudential Financial that found most so-called “mass affluent” Americans lack adequate savings or realistic plans for their golden years.

The insurance giant’s latest study reveals that workers earning between $75,000 and $300,000 annually — a group that includes teachers, police officers, and mid-level state employees throughout New Jersey — dramatically underestimate how much money they’ll need to maintain their lifestyle after leaving the workforce.

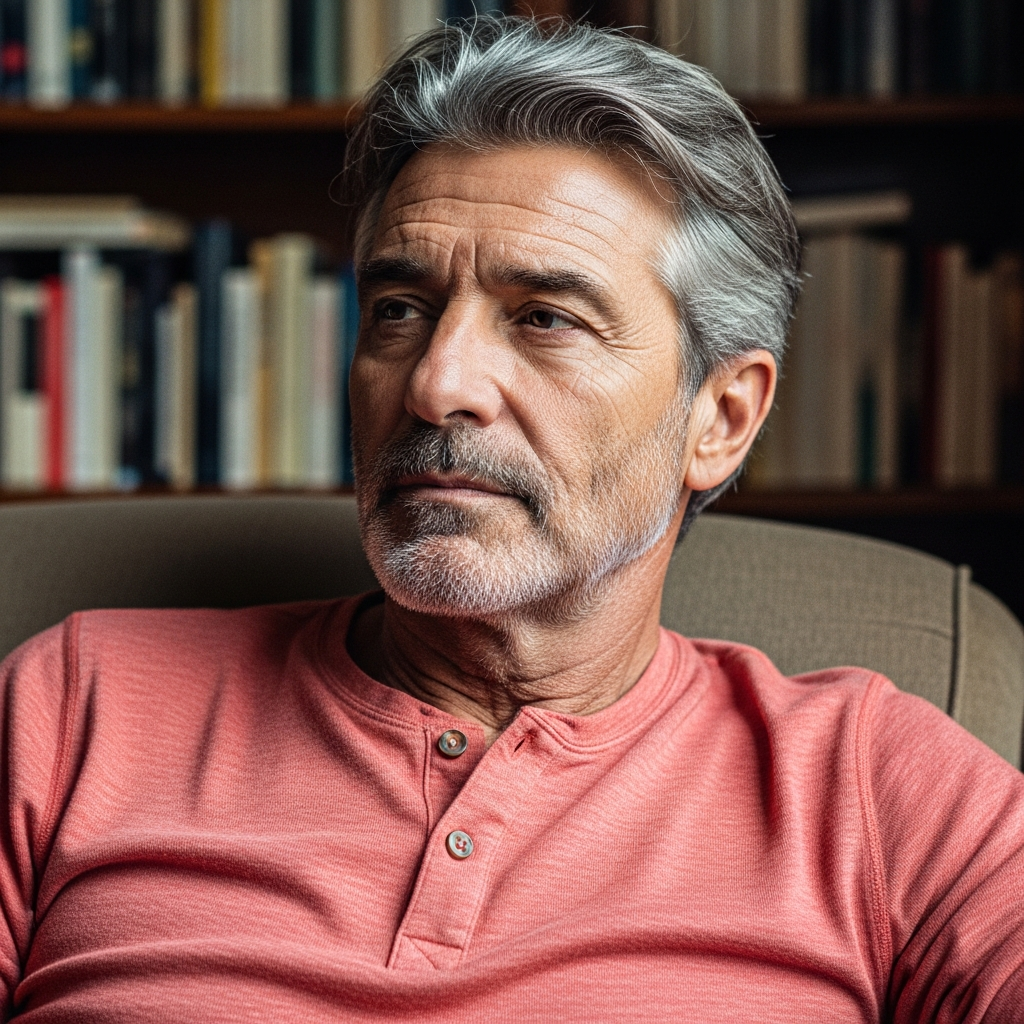

David Blanchett, Prudential’s head of retirement research, said the findings should alarm policymakers and employers across the Garden State, where the cost of living continues to climb while traditional pension benefits shrink.

“These are people who look financially secure on paper, but scratch beneath the surface and you’ll find they’re making critical mistakes that will hurt them down the road,” Blanchett said during a recent interview. “This isn’t about poverty-level workers — this is about your neighbor, your kid’s teacher, the guy who fixes your car.”

The study surveyed 1,200 Americans nationwide, but Blanchett said the results mirror what Prudential sees in its home market of New Jersey, where high property taxes and housing costs eat up larger portions of middle-class paychecks.

Key findings include that 60 percent of mass affluent workers believe they can maintain their current standard of living on just half their pre-retirement income — a target most financial planners consider dangerously low. The traditional rule of thumb suggests retirees need 70 to 90 percent of their working income to avoid significant lifestyle changes.

Even more troubling, nearly 40 percent of respondents admitted they haven’t calculated how much money they’ll actually need in retirement, despite being within 10 to 15 years of leaving the workforce.

“People are guessing about the most important financial decision of their lives,” Blanchett said. “That’s not a strategy — that’s hoping for the best.”

The research comes as New Jersey grapples with broader questions about economic security for middle-class families. State employees have watched their pension benefits erode over the past decade, while private sector workers increasingly rely on 401(k) plans that shift investment risk from employers to individuals.

Governor-elect Mikie Sherrill, who won election in November, campaigned on promises to strengthen the state’s middle class but faces budget constraints that may limit her options for addressing retirement security.

Prudential’s study found that mass affluent workers make several common mistakes that compound over time. Many underestimate how long they’ll live, failing to plan for 20 or 30 years of retirement expenses. Others assume Medicare will cover all their healthcare costs, ignoring potential long-term care needs that can devastate savings.

The research also revealed geographic blind spots. Workers in high-cost states like New Jersey often assume they’ll move somewhere cheaper when they retire, but many end up staying put due to family ties or healthcare needs — forcing them to stretch inadequate savings in expensive markets.

“Everyone thinks they’re going to retire to Florida or North Carolina, but a lot of people never leave,” Blanchett said. “Suddenly that $500,000 in your 401(k) has to last 25 years in Bergen County, not 25 years in Jacksonville.”

Prudential’s findings echo warnings from other financial services companies, but carry extra weight given the firm’s 150-year history in Newark and its role managing retirement plans for thousands of New Jersey employers.

The company manages more than $1.4 trillion in assets globally, including pension funds for numerous New Jersey municipalities and private employers throughout the state. That gives Prudential researchers detailed insight into how middle-class workers save — and where they fall short.

Blanchett said the mass affluent group faces unique psychological barriers that prevent better planning. Unlike lower-income workers, who know they need help, or wealthy individuals, who can afford professional advice, middle-class earners often assume they’re doing fine without taking a hard look at the numbers.

“There’s a dangerous middle ground where people think they’re financially literate because they have a 401(k) and a savings account,” he said. “But retirement planning is complicated, and small mistakes compound over decades.”

The study recommends several steps for workers still in their peak earning years. First, calculate actual retirement expenses rather than relying on broad percentage rules. Second, max out employer matching contributions and gradually increase savings rates. Third, consider working longer or taking part-time jobs in early retirement to stretch savings.

For New Jersey workers specifically, Blanchett emphasized the importance of tax planning. The state’s high income taxes make traditional 401(k) contributions especially valuable for current workers, while Roth conversions might make sense for retirees who move to states with lower tax rates.

The research also highlighted opportunities for employers and state policymakers to address retirement security gaps. Automatic enrollment in retirement plans, better financial education programs, and expanded access to professional advice could help middle-class workers avoid common pitfalls.

“This isn’t a problem that solves itself,” Blanchett said. “Workers need better tools, better information, and sometimes a reality check about what retirement actually costs.”

Prudential plans to release additional research this spring focusing specifically on retirement preparedness among public sector workers in high-cost states like New Jersey. That study will examine how pension benefit cuts and rising healthcare costs affect teachers, police officers, and other government employees approaching retirement.

For now, Blanchett’s message remains simple: middle-class workers who think they’re prepared for retirement should double-check their math before it’s too late to course-correct.

“The good news is that most of these people still have time to fix their mistakes,” he said. “The bad news is that time is running out faster than they think.”