Camden Schools Rise While Trenton Falls Behind

Two struggling districts took different paths. Camden's state takeover brought results while Trenton's local control hasn't stopped the decline.

Camden’s public schools posted their highest graduation rates in decades last year while Trenton’s students continue falling behind state averages — a stark divide between two cities that started with similar challenges but took different paths to reform.

Camden High School’s graduation rate hit 89% in 2024, up from 49% when the state took control of the district in 2013. Meanwhile, Trenton’s rate dropped to 73%, down from 78% five years ago, according to state Department of Education data.

The contrast shows how New Jersey’s approach to failing districts produces wildly different results depending on who’s making the decisions. Camden surrendered local control to state-appointed officials who closed schools, fired staff and brought in charter operators. Trenton kept its elected school board and fought state oversight at every turn.

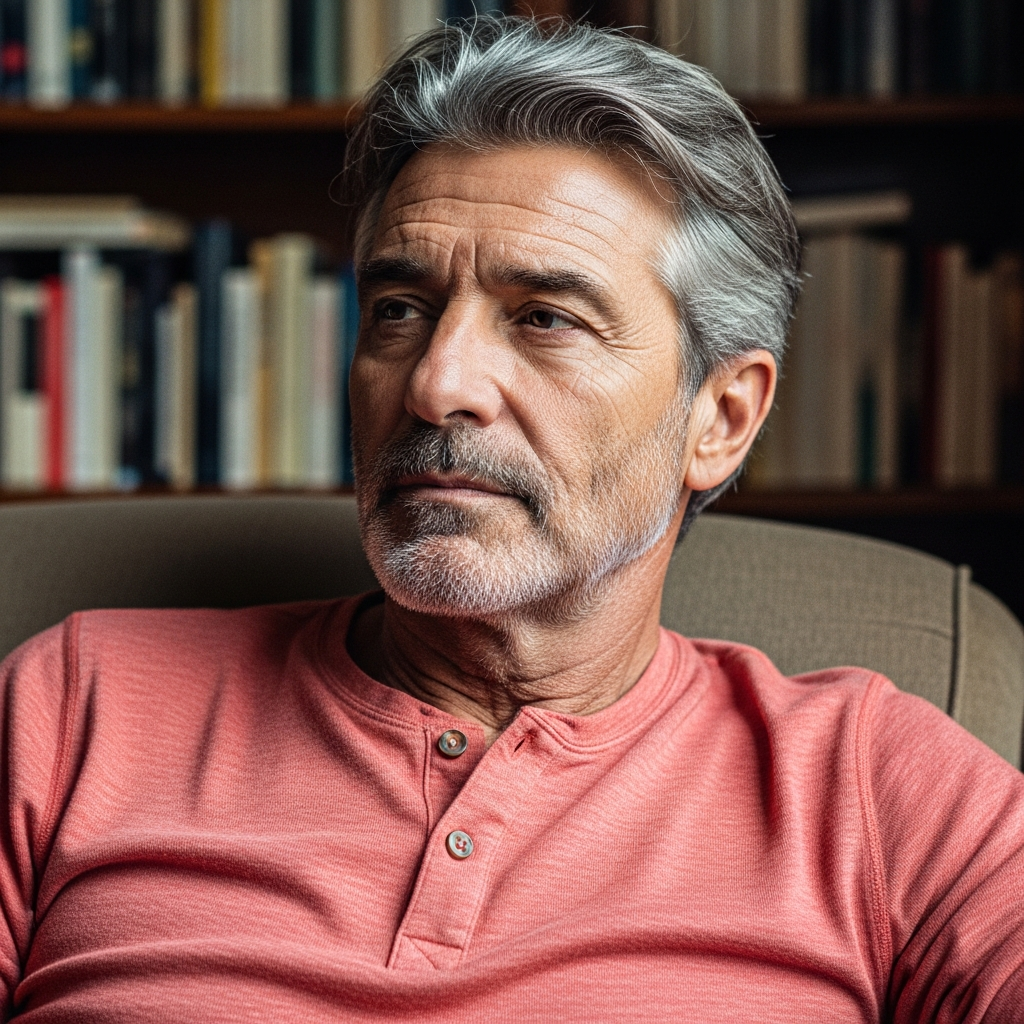

“Camden made the hard choices early,” said David Hespe, who served as state education commissioner during Camden’s takeover. “Trenton’s been fighting change for twenty years.”

Both districts serve similar populations — majority Black and Latino students from low-income families — but their trajectories diverged after Camden accepted full state intervention in 2013. The state closed underperforming schools, expanded successful charter programs and replaced the central administration.

Trenton resisted similar measures. The district’s school board sued the state multiple times to block charter school expansions and rejected proposals to close failing elementary schools. Board meetings regularly devolved into shouting matches between parents and officials.

The results speak for themselves. Camden students scored 15 points higher on state math assessments in 2024 compared to 2018. Trenton students dropped 8 points over the same period. Camden’s chronic absenteeism rate fell from 35% to 22%. Trenton’s rose from 28% to 34%.

“We had to break some eggs to make the omelet,” said Katrina McCombs, Camden’s state-appointed superintendent since 2018. “That meant making unpopular decisions about which schools stayed open and which programs got funding.”

The improvements came with political costs. Camden teachers union fought layoffs and school closures through 2016. Community groups accused state officials of ignoring parent input on curriculum changes. Several charter operators faced criticism for aggressive discipline policies.

But test scores and graduation rates kept climbing. Camden’s English language arts proficiency doubled from 18% in 2015 to 36% in 2024. The district added AP courses at every high school and expanded career training programs that connect directly to local employers.

Trenton took a different approach. The school board maintained local control despite years of poor performance and financial mismanagement. State monitors provided oversight but couldn’t override board decisions on major policy changes.

That resistance to outside pressure may face new challenges as changing leadership takes hold in Trenton. Governor-elect Mikie Sherrill’s transition team includes several education reformers who supported Camden’s transformation.

Trenton Superintendent Fred McDowell defended his district’s record, pointing to recent investments in pre-K programs and teacher training. The district opened two new elementary schools in 2023 and expanded summer learning programs.

“We’re making progress, but we’re doing it the right way by keeping our community involved in every decision,” McDowell said. “Camden gave up local control. We refused to abandon our parents and teachers.”

The data suggests that approach isn’t working. Trenton spends $24,000 per student annually compared to Camden’s $22,000, but produces worse outcomes across every major metric. Only 28% of Trenton third-graders read at grade level compared to 41% in Camden.

State education officials privately acknowledge the Camden model works better but costs political capital. Taking over local districts requires sustained commitment through multiple election cycles and inevitably generates community backlash.

“Every district wants Camden’s results, but nobody wants Camden’s medicine,” said one state official who requested anonymity to discuss sensitive negotiations with struggling districts.

The success in Camden created a template that other failing districts could follow. Elizabeth and Paterson both accepted expanded state oversight in recent years rather than face full takeovers. Early results show modest improvements in both cities.

Trenton faces growing pressure to accept similar changes. State monitoring reports from 2024 cite persistent problems with financial management, academic performance and board governance. The district’s bond rating dropped to junk status last year.

McCombs argued that Camden’s turnaround required specific conditions that don’t exist everywhere — strong charter school operators willing to expand, community leaders ready to support difficult changes, and state officials committed to long-term investment.

“You can’t just drop this model anywhere and expect it to work,” she said. “But the alternative is watching kids fail year after year while adults argue about who’s in charge.”

The contrast between Camden and Trenton will likely influence broader discussions about education policy as New Jersey lawmakers debate charter school funding and district accountability measures. Camden’s success gives reformers ammunition while Trenton’s struggles highlight the limits of local control.

Both districts still face challenges. Camden’s gains remain fragile, with many students still performing below grade level. Trenton’s problems run deeper than test scores, including aging buildings, staff turnover and community distrust.

But the gap between them keeps widening. Camden students now outperform state averages on several measures while Trenton lags further behind each year. The question isn’t whether state intervention works — it’s whether other districts will accept the trade-offs that success requires.